Satellite data has shed new light on seismic hazard in one of the world’s most deadly earthquake zones.

Published today in Nature Communications, the COMET study describes how tectonic strain builds up along Turkey’s North Anatolian Fault at a remarkably steady rate.

This means that present-day measurements can not only reflect past and future strain accumulation, but also provide vital information on events still to come.

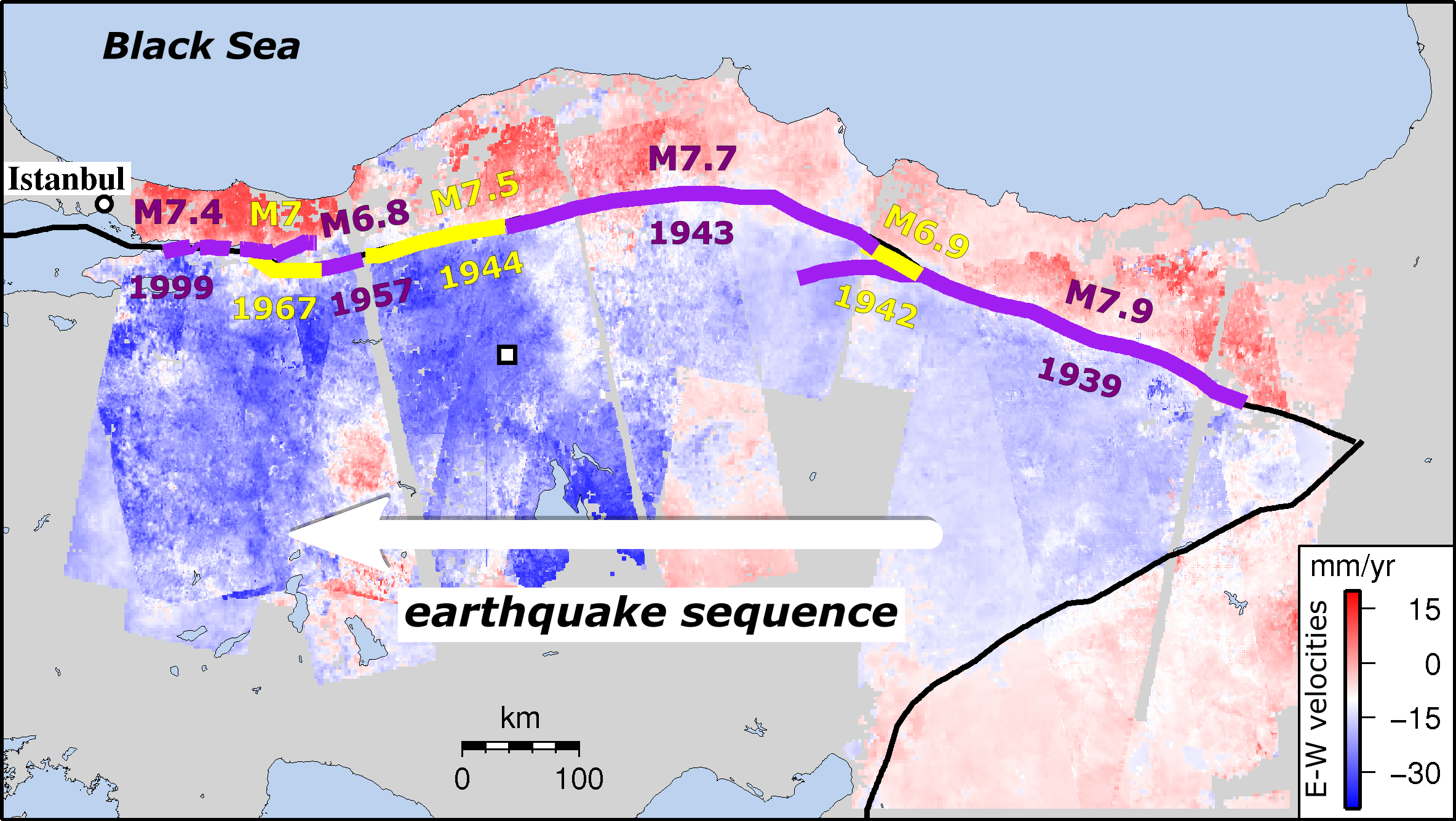

The strain, which builds up as Turkey is squeezed between three major tectonic plates, has caused almost the entire length of the fault to rupture since 1939 in a series of major earthquakes gradually migrating east-west towards Istanbul.

Led by COMET PhD student Ekbal Hussain[1], the team used satellite images from the European Space Agency’s Envisat mission to identify tiny ground movements at earthquake locations along the fault.

Dr Hussain explained: “Because we know so much about the fault’s recent history, we could look at the strain build up at specific places knowing how much time had passed since the last earthquake.”

The 600-plus satellite images, taken between 2002 and 2010, provided insights into the equivalent of 250 years of the fault’s earthquake repeat cycle.

Remarkably, apart from the ten years immediately after an earthquake, strain rates levelled out at about 0.5 microstrain per year, equivalent to 50mm over a 100km region, regardless of where or when the last earthquake took place.

Dr Hussain added: “This means that the strain rates we measure over the short term can also reflect what’s happening in the longer term, telling us how much energy is being stored on the fault and could eventually be released in an earthquake.”

Until the satellite era, it was difficult to get a clear picture of how strain built up on the fault. Now, satellites like Envisat, alongside the newer Sentinel-1 mission, can detect ground movements of less than a millimetre, indicating how and where strain is accumulating.

The findings suggest that some existing hazard assessment models, which presume that strain rates vary over time, need to be rethought. This is especially true for regions where there are long gaps between earthquakes, such as the Himalayas.

Co-author and COMET Director Tim Wright said: “Discovering this consistent strain accumulation will help us to reassess how we model seismic hazards, as well as improving understanding of the earthquake cycle worldwide.”

The full paper is: Hussain et al. (2018) Constant strain accumulation rate between major earthquakes on the North Anatolian Fault, Nature Communications, doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03739-2

[1] Now Remote Sensing Scientist at BGS Keyworth. Dr Hussain is available for comment (ekhuss@bgs.ac.uk).