Around 20 scientists gathered at the University of Leeds recently to share their knowledge and their views on how magmatic activity can be understood and reproduced by models of volcanic processes.

Fourteen COMET members, including scientists, research staff and students, were joined by experts in various fields of volcanology from other world-leading institutions such as the United States Geological Survey, the University of Geneva and the University of Liverpool.

At the workshop we discussed the numerous challenges we face when we try to experimentally replicate natural processes such as those occurring at volcanoes. The most important limitation is that we can exclusively witness and measure what happens at the surface of the volcanoes, and only indirectly infer what goes on beneath them.

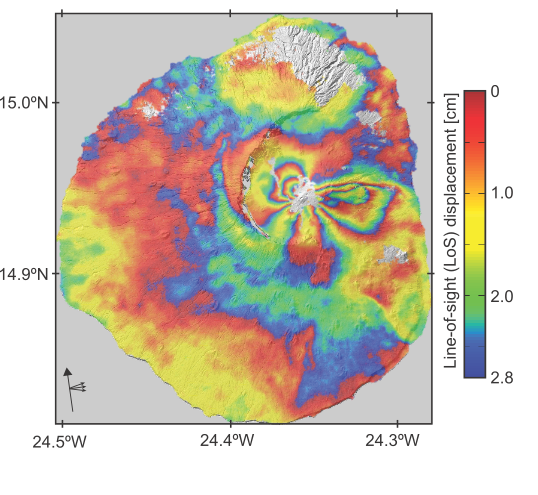

There are many different techniques commonly used to take the pulse of the magmatic activity: we measure how the volcanic edifices deform, we record seismic waves coming from and travelling through the magmatic systems, we collect and analyse lava and ash samples during eruptions, we measure the concentration of gases emitted by volcanic vents etc.

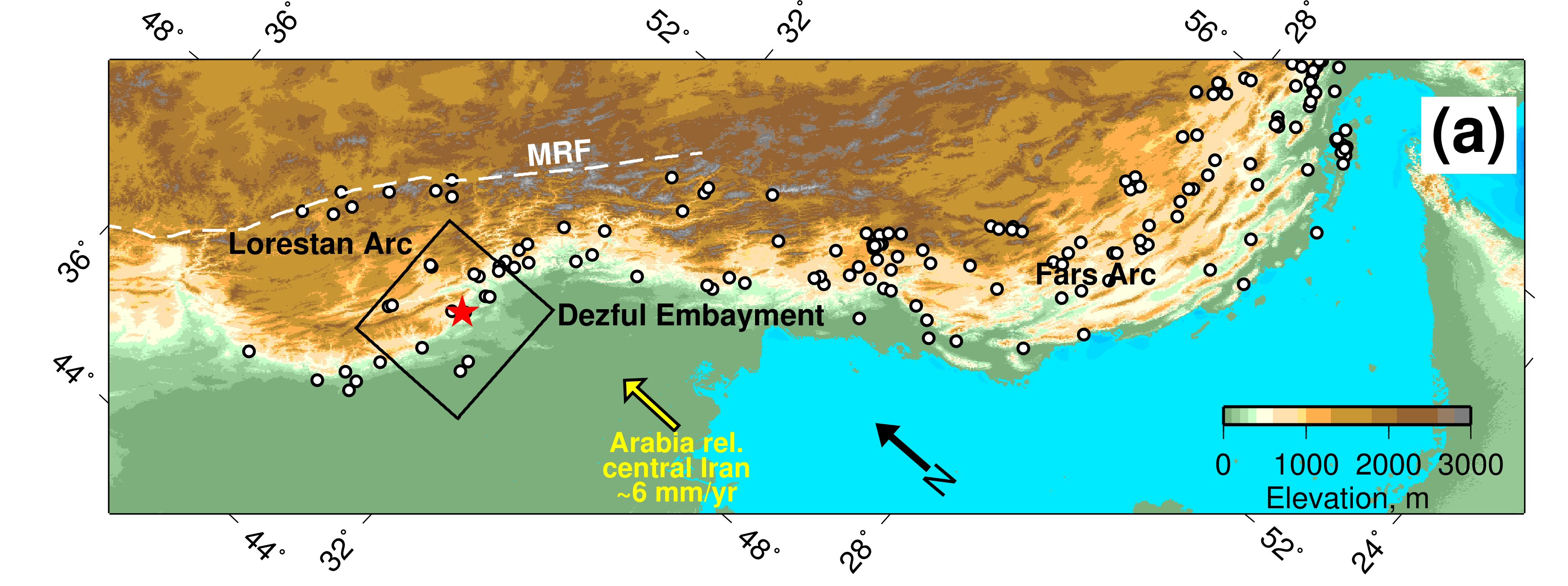

The rapid expansion and improvement of satellite Earth Observation (EO) techniques (such as radar interferometry to measure deformation, infrared atmospheric sounding to measure gas emissions etc.) offers further opportunities to study magmatic processes at a global scale.

Although each technique can shed light on one or more volcanic processes, the highest chance of truly understanding what controls the magmatic activity happens when all the measurements and information are analysed together.

The use of a multi-disciplinary approach was the key element of the COMET workshop and all participants agreed that future research in volcanology must move in this direction. Conceptual and numerical models of how magma is stored beneath the surface must be able to reconcile the observed deformation, the amount of gasses released in the atmosphere and the physical/chemical properties of the erupted products. Models of how magma reaches the surface during eruptions need to explain the seismic signature of magma ascent, be compatible with the mechanical properties of volcanic rocks, and consider magma as a multi-phase fluid containing gas, liquid and crystals.

During our workshop, we identified several potential research projects that will be developed in the coming months and that will imply the use of information from different disciplines of volcanology. For example, we aim to globally classify active volcanoes on the basis of their behaviours in terms of deformation and gas emissions. Much effort will also be put in understanding the characteristics of magma reservoirs, moving from conceptual models of simple liquid-filled cavities to complex, multi-phase, dynamic systems.

Finally, specific volcanoes where COMET scientists already have access to long records of geophysical, geochemical and petrological data (for example Soufriere Hills Volcano in Montserrat or Kilauea Volcano in Hawaii) will be used as natural laboratories. At these locations, we will test models that try to reproduce processes ranging from specific eruptive behaviours to long-term magma supply to the volcanoes.

For further information, contact Dr Marco Bagnardi [email protected]