Laura Wainman (University of Leeds)

“Bhūkampa! Bhūkampa!” “Earthquake!” the shouts echo around the classroom. “I would have won!” a boy exclaims, begrudgingly sliding his counter back by 5. Students gather around the game board in collective frustration, determined to quickly make up for their lost points. The surrounding valley, however, remains peaceful; we’re sat outside the classroom, basking in the first warm days of the dry season. There is no hint of the earthquake that’s just happened, or the one that may be yet to come.

The game itself developed collaboratively, inspired by other so-called “Serious games” used in academic outreach, as well as by larger organisations such as the Red Cross. The underlying principle is to replicate, in some way, a physical or social reality. Through play, the participants learn more about this reality and develop strategies for dealing with the challenges it presents. The Disaster Ready! game aims to encapsulate this as a disaster risk reduction (DRR) education tool – being set within a rural Nepali community, players must move around the village, performing individual and collective actions, as well as acquiring response and recovery cards for when disaster strikes. Actions gain players points and include things such as packing an emergency bag, practicing “drop, cover, hold”, or making a collective emergency plan for their village. Disasters are triggered randomly by landing on red tiles, forcing players to draw a card from the hazard deck containing earthquakes ranging in magnitude from M1-M7.

Across all the sessions I delivered during my time in Nepal, the overwhelming response to the Disaster Ready! game was one of curiosity and enthusiasm. Equivalent lecture style presentations on earthquake risk and preparedness, although similar in content, were often met with reserved interest, or polite disinterest. These presentations, me at the front, the audience facing, often felt othering – I was an outsider coming to lecture, not to listen. Playing the game went some way to dissolving these boundaries. The focus switched from my theoretical knowledge, well-intentioned but often naïve in the face of the everyday challenges communities are facing to the experiences of those who live with earthquake risk every day. Shared stories of worry and anxiety, of soup split by ground shaking, of laughter over how many nappies could fit in an emergency bag, replaced what could have been cold and distant knowledge. The game served to humanise the experience of living with earthquake risk and in doing so connected people over their shared realities, generating conversations around what it means to be prepared, both on an individual and community level. The enthusiasm of the children was especially contagious, and the highlight of most sessions was watching their eyes light up as they unpacked the game to begin playing. The Nepali education system, particularly in the most rural areas, is severely underfunded and poorly resourced. Some teachers lack any formal training and most rely on rote learning methods to instil information in their students. Noisy, dilapidated classrooms offer a poor learning environment, and many students struggle to concentrate as a result. This makes learning through a game, like Disaster Ready!, novel and exciting. It is an entirely new approach for many students, encouraging active participation, role play, decision making, and a chance for critical discussion in a system where children’s voices are rarely heard.

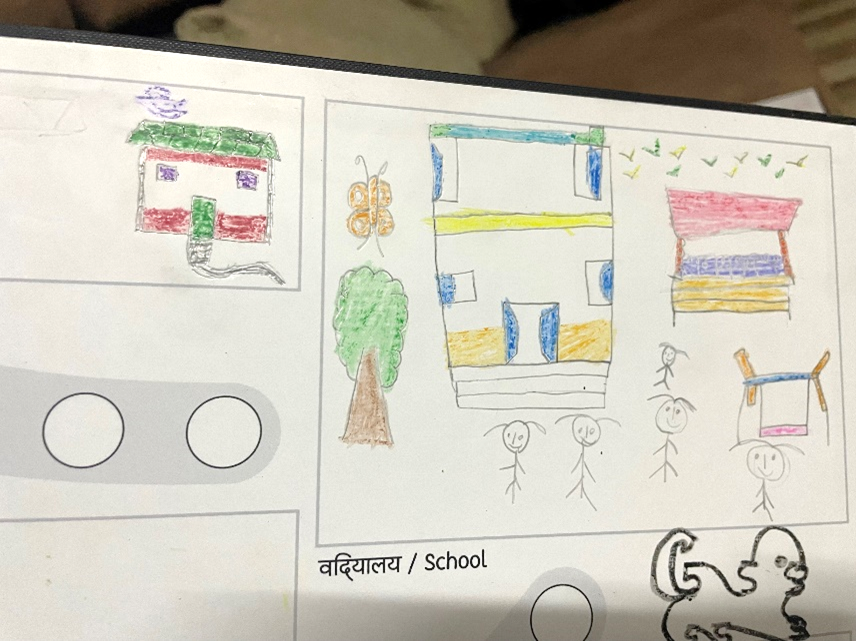

The game was so captivating in part due to its illustrations. These were done by artist Micheal Heap, who’s based at the Leeds Arts University. The initial illustrations were our “best guess” of how to represent a Nepali village. With neither of us having actually been to Nepal before, we based our drawings of houses and schools on those we could find on the internet. Of course, we also knew that this approach would fall short of capturing the vibrancy and life of Nepal, or the cultural cues known only to a native Nepali person. Because of this, we were keen to use Phase I of the trip to understand, artistically, how we could improve the game and embed it within a Nepali context. To do this, I ran a series of workshops with the children whilst in Nepal, encouraging them to draw their houses, villages, and surrounding environment on blank versions of the game boards. What we got back was a wealth of beautiful illustrations – dogs in characteristic Nepali style, flowers, butterflies, adorned temples, rice fields and tractors. These are the images that will bring the game to life.

Having returned from Nepal, the Disaster Ready! project is now in Phase II – re-development. This includes revising the illustrations on the board and cards based on the student’s drawings. We hope this will more fully capture the context of Nepal and give the students a sense of ownership over the game when it is sent back to them. Connecting with Nepali educators and teachers has also led to invaluable input into the game. This includes revising my attempts at Nepali translations – currently “passable” but overly formal for younger children and, I’m told, with an alarming lack of grammar. Phase II will also see the expansion of the game into other hazards such as wildfires, floods, and landslides. These hazards are felt more frequently than earthquakes by many communities in Nepal but can be just as devasting. The effects of climate change are anticipated to worsen the frequency and severity of these events in Nepal over the next few decades and the country is considered highly vulnerable to climate disasters by the UN.

Building these additional hazards into the Disaster Ready! game is therefore critical to a more holistic approach to community preparedness and risk education. Whilst the challenges of living with the threat of multiple hazards can be many, so too can the opportunities to increase preparedness and resilience to multiple events simultaneously. For example, an emergency bag is useful following an earthquake, but also after a flood, or whilst evacuating due to a wildfire. A community evacuation procedure can be adapted to multiple eventualities and even in its formation may strengthen the sense of collective preparedness and decision-making capacity within the community. This line of thinking can be extended well beyond the traditional disaster risk and preparedness remit. Many communities expressed that their primary vulnerability to disasters such as earthquakes, was in fact their everyday food precarity, lack of access to clean water, and the struggle to survive on incomes well below the poverty line. Asking people to pack non-perishable food in an emergency bag is hardly reasonable when they have insufficient food to eat that evening. In this sense, for many communities, installing a water tank, educating women, or providing agricultural training would do as much for disaster resilience as any DRR-specific actions, whilst simultaneously improving the day-to-day quality of life for many.

The future of the Disaster Ready! game remains somewhat uncertain, caught between ambitions for greater impact and a lack of funding to support our vision. Whilst in Nepal, many students and teachers asked to keep copies of the game, expressing their support for its continued use within their DRR curriculums. The five copies of the game that I took out with me were left for teachers and educators to continue to use, although ultimately, these will have only a very small impact in filling the large void of DRR resources in Nepal. This is where the vision for Phase III of the project comes in – expansion. What if we could print 150 copies of the game, to be distributed to 50 schools in Nepal? What impact could that have? Over 5 years this would translate to 15,000 students having played the Disaster Ready! game. By 2050 – the year that Nepal aims to be “disaster resilient” – over 75,000. These numbers have the potential to make a significant impact, locally, regionally, and maybe even nationally. Crucial to the success of any future phases of this project is of course partnering with and transferring autonomy over the game to local stakeholders. Phase III would therefore be carried out with an in-country partner such as an NGO or academic institution in Nepal, key to monitoring the use of the game over the next few years and evaluating its impact.

One of my final experiences in Nepal was to visit the village of Langtang, situated to the north of Kathmandu and accessible only by helicopter or 3 days of trekking through the jungle. For me, this experience came to represent many of the challenges that persist around delivering DRR education, both in Nepal and globally. But it also inspired me – this work is meaningful, necessary, and should be something that I strive to do throughout my career. The village of Langtang was one of the worst affected by the 2015 Gorkha earthquake, with over 300 casualties due to a landslide which all but wiped out the village. Walking along the hiking path through the valley you pass by what remains, now buried under 20 metres of rubble. My guide, Ram, explained that the landslide happened 30 minutes after the initial earthquake and that ultimately, the actions that people took in those intervening minutes proved critical. Those who were younger, and had generally had more access to education, knew that following the earthquake they should move into open space because of the increased risk of a landslide. These few people survived. But most people in the community, many of whom had never had the chance to engage with any DRR outreach or education, stayed behind. Sheltering in their homes, despite surviving the earthquake, they were left directly in the path of the landslide. The knowledge that saved lives, and that could have saved more if it had only been taught and shared more widely, can fundamentally be reduced down to only two sentences: “Landslide risk is higher following an earthquake. Move to open space and away from steep slopes”.

How many thousands of papers and conference presentations have been produced on the tectonics of the Himalayas? How many field campaigns have drawn on local knowledge and relied on the resources of local communities? And yet, for so many living in this region they did not have the most fundamental, two sentences of knowledge that would have kept them safe. This is in part the result of decades of so-called “helicopter research”, predominantly out of western universities and institutions. If colonial-era science was used to justify the exploitation of resources, then perhaps science under neocolonialism is marked by the extraction of knowledge without a commitment to reciprocity, dialogue, or delivering concrete benefit to communities in whose backyards we are working. This is one of my most lasting impressions – that sharing knowledge, in a way that truly empowers people and communities to understand their environment and to make their own decisions on preparedness and resilience, is fundamental to doing both DRR work and science well. The geoscience community has such a wealth of knowledge and resources, but currently this is struggling to reach the people that need it most. I sincerely hope that projects like Disaster Ready! will contribute to towards bridging this gap.

Want to support the project?

We are currently looking for funding to support Phase III of the project. If you know of suitable funding streams which could be worth applying to please reach out! Or if you have experience of DRR outreach, especially through “serious games” then we would love to collaborate and hear more.

Acknowledgements

A warm thank you to all those who have and continue to support the Disaster Ready! Project: Soroptimist International Leeds, COMET, Volunteers Initiative Nepal (VIN), Dr Claire Quinn, Dr Laura Gregory, Dr Peter Sutoris, Micheal Heap, and Nirmala Karki.